Data Festival Tilburg Introduction

Tangible situations: Representing data as music

The notion that music is essentially just data, is not new in itself. And it is gaining more supporters every day: Bit Torrents are channeling Gigabytes of sounds from one user to another. And the leading label of the new millenium is iTunes – run by a Software- and Hardware-Developer. So the whole notion that sound can be represented by computer files is not just a fanciful idea, it has become an everyday reality. More and more, artists are coming to terms with this reality – or, in some cases, they are making the struggle of coming to terms with this reality part of their art. If music is data and can be described by machines, doesn’t that limit the space for human creativity?

That is certainly still quite a bit off, but I was reminded of this when I recently found out about uplaya. Uplaya is a program developed in the USA, which is supposedly capable of determining whether a particular song has hit potential or not. Its mechanisms are simple: You upload a track to their server and only a couple of seconds later, the algorithm has calculated whether you’ve got a winner in your hands or a flop. Now it’s not really all that surprising that there is a market for these kind of gadgets. Especially in times, when everybody can record and publish their songs, every solution to make you stand out from the masses, no matter how rediculous or improbable that solution may be, is welcome. What is a lot more interesting, however, is that uplaya apparently predicted that Norah Jones‘ debut album, which was recorded when she was a complete nobody, would go on to take the charts by storm – and it did.

What this Software accepts is not that music is data – but that music can be represented by digital data. And digital data, in turn, can be quantised and statistically analysed. So it can evaluate which combination of chord changes, beats, melodies, lyrics even – have been succesful in the past. After that, it then procedes to compare a particular song with these clusters of hit songs and finally arrives at a conclusion. It doesn’t rule out human creativity just yet – but it does claim that the way we perceive and listen to music is bound by a set of fundamental rules, which in turn can be put into numbers.

Another interesting development with a similar thought behind it was initiated by Pete Townsend of The Who. He had an idea for a program called „The Method“, which was able to generate musical portraits of its users. You would upload three things: A photograph of yourself, a personal sound which you liked (maybe your doorbell or your phone ringing) as well as a short musical segment (a song by Norah Jones). After that, the Software would create a piece of music which would essentially tell you who you were in sound. Townsend had great plans for his pet-project, because he thought that, in the end, you could use it as part of an online community. So instead of just having your picture on your facebook account, you would also have your very own personal tune to tell other people who you are in just a few seconds time.

Still today, both projects sound a bit alien. What makes us scratch our head, mostly, is that music could ever represent something other than what it essentially is: organised sound. But if you really think about it, in their own way, a CD, LP, Tape or MP3-file are also not entirely representative. Recorded music is also a translation of a real situation into a very, very condensed space. All the elements that make up a live performance – sweat, cigarette-smoke, all the noises from the room, your uncomfortable chair or your back aching from standing all night, that one beer you’ve had too many, the way the musicians act on stage, all this can physically not be transmitted in the recording stages. And yet, some select live-albums are capable of somehow making you feel all this nonetheless. Even on some of the live albums of German electronica-pioneer Klaus Schulze, which were recorded straight to a hard drive without any kind of ambient sounds from the concert hall, convey some of this tension. So obviously, sound can imply much more than just what the ear can hear.

And then there’s an even more important aspect . Questions such as these are no longer academic or eccentric. What someone like Roland Etzin is doing – freezing sound and trying to capture the sonic characteristics of a photograph – might have seemed wild a couple of years ago. Now there are plenty of Software-programs that will do the trick and they are not just easy to use but affordable as well. The point is therefore no longer whether it can be done. But whether it can be done in a way that seems to be genuine, emotionally engaging and sensible. We’re already far past the post of mere experimentation. A plethora of artists are dealing with the relationship between sound and information their work is firmly grounded in very tangible situations and deal with very concrete artistic challenges:

* Andrea Polli has tried to sonify very particular conditions on Antarctica, inspired by her stay there.

* Derek Holzer was frustrated with traditional ways of performing music and has turned to using light – another carrier of information – to arrive at intuitive experiences.

* Achim Wollscheid is interested in how music is always both input and output, how it can or rather should not be separated from its inherent reaction.

* Roland Etzin, as has been mentioned, was looking for a way to create the sonic equivalent of a particular photographic moment.

* Christoph Korn is taking a slightly different stance by drawing an analogy between collecting data and the process of composing and how different they are – and that, in composing, some of the hidden data, the information you’re withholding from your audience, can be the most effective part.

* Lasse-Marc Riek has documented the sound properties of churches in Tilburg, questioning the idea of churches being spaces for silence, asking questions such as: When do these noises turn into noise? Is it actually okay if there were complete silence? How is the idea of silence picked up by visitors, how are they reacting to it?

Contrary to what the developers of that hit-software mentioned at the beginning are promsing, though, there are no definitive answers. There’s a quote by Jeff Tweedy of Wilco which nicely delineates the territory still left to human creativity: „Music is just data until listeners put that music back together with their own ears, their mind, their subjective experience.” As such, you don’t need to worry that all you will be served in the furure is just software, algorithms, concepts and algebra. It is always, above all, music. (By Tobias Fischer / Download PDF)

Data Festival Tilburg Artist Introductions

* Andrea Polli

Needless to say Andrea Polli’s trip to Antarctica was a once-in-a-lifetime experience. There was intense sunlight 24 hours a day, the most clean air you could imagine and an environment which she describes as a natural „hifi soundscape“, a place so quiet that it gives you the feeling of hearing your own nervous system.

There is an intriguing quote by computer scientis Paul Dourish which perfectly defines her work: „There is more information available at our fingertips during a walk in the woods than in any computer system…”. There is an immediate connection to the Antarctica project: One part of her work there involved learning how weather and climate information is gathered. She expected this to be done using automated weather stations, which are basically nothing but a little box mounted on a mast, containing a data device, a battery and the meteorological sensors. Truth be told, these automatic station have become essential. And yet, as it turned out, it is still mainly people who are responsible for the largest part of the workload. This seemed to be running against rational logic, because it is much more costly and even outright dangerous to send meteorologists there. Still, the outcome of her analysis did not provide her with a clear answer. As a matter of fact, the solution remained entirely intangible. So to get back to the quote by Paul Dourish, the amount of information that is out there and that you’re taking in through your senses is incomprehensibly vast. And apparently, we’re processing a lot of it without actually being aware of it. This has in turn made an important contribution to her work as an artist. In her sound pieces, the notion of an intangible element – the things you can not explain, can not quantify, can not intellectually understand – has become a key.

In her work „Sonic Antarctica“, also released as a CD on Gruenrekorder, this is becoming clearly apparent. Andrea programs software which will make use of numerical values to change particular aspects of samples. You can think of how the wind produces sound: It moves through different objects and thereby changes their timbre. So to get back to the question of the relationship between music and data: To Andrea, this data has a particular form, a shape, which will become visible in the music. What you are therefore hearing is a particular quality of Antarctica as music.

* Christoph Korn

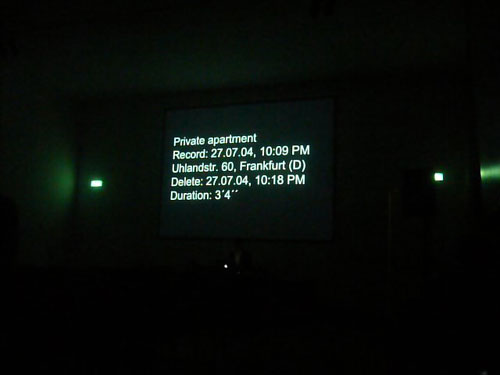

As mentioned in the introductory essay, not all questions regarding the relationship between music and data can be answered as clearly as on a hit song. This is certainly true for the work of Christoph Korn and especially so for some of his most recent pieces, including „Waldstücke“, an online composition, „I speak this text“, originally a radio play as well as „Series Invisible“ the first edition of which was published last year. That release alone made some people wonder. Essentially, it was nothing but a little book which contained textual descriptions of recordings which had been deleted – no audio, no sound, just descriptions of the place where the audio and the sound came from. It got a noteworthy prize and some comparisons to the emperor’s new clothes – certainly one of the more controversial things Gruenrekorder have published over the years.

Korn’s approach touches upon an intriguing aspect of the idea of sound as data – or perhaps also on what makes music different from data. Usually, when composing, one accumulates material. One starts with nothing and arrive at something. One adds elements, like a painter adds colour to the canvas, the way he would add lines, circles or concrete objects like people, cats, dogs. Here, however, everything is about taking things away. It is about starting with something and ending up with a lot less. This is, of course, a tradition the minimalists have employed for centuries, but it is somehow becoming very contemporary through the thought of sonic digitisation. If music is indeed data, then the question is: What is really hidden behind the ones and zeros?

* Achim Wollscheid

Reactions are a key element of Achim Wollscheid’s approach. One may possibly not be able to tell from his current work but he has a background in Rock music and one of the worst thoughts to him has always been the way classical music is presented in public: As a passive consumption of what is happening on stage without any kind of feedback loop – except perhaps polite applause at the end. On the contrary, during a Rock concert, the way an audience reacts will influence what one is doing, creating at least partially the sensation of co-operating on something together. This ideal has remained important to him throughout the years.

* Roland Etzin

Software transforming an image into sound has become all but ubiquitious. And yet, it was exactly one of these programs which inspired Roland Etzin to come up with „Image Data“. To Roland, what made this program interesting was not so much the musical quality of the result, but rather its structure – and how much you could somehow detect analogies in the music to the way the photograph was organised.

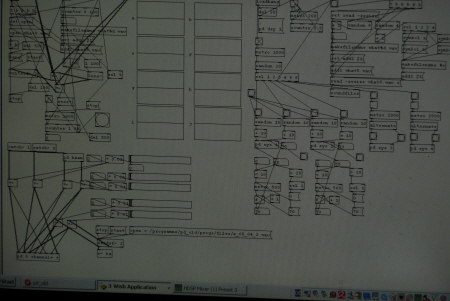

So the point of „Image Data“ is not to prove that you can transform image into sound. But to have a look at how image and sound correspond with each other. For each sequence, Roland is only using site-specific material – meaning if you have a scene in the forrest, then the only material which is used for that piece are sounds and images taken on that spot. There are many different ways of processing the material, for example by translating images to digital files and then have these files trigger Software-Synthesizers. These Software-Synthesizers, meanwhile, will only use sound sources culled from field recordings. So it’s a game of lots and lots of connections, of ideas which are all related to each other in some way and which will hopefully, lead to a clearer insight into the way visual and acoustic properties are related.

„Image Data“ is also a good way of showing how you can make use of the data properties of sound to arrive at fresh musical results. In the run-up to the Data festival, Roland mentioned that he was excited himself about where the different transformations would take him. What it does is replace the entirely subjective experience of the way one remembers what something sounded like in one’s mind with a somewhat more objective picture, which can be discussed by different people. Each of these angles deepens the impact one would get from just looking at a silent, static picture or a pure field recording. Which also goes to prove that even if music is nothing but data, it is still all about emotion.

* Derek Holzer

Even today, Derek Holzer’s technique of using overhead projectors to trigger sound looks futuristic. In reality, as he’s pointed out several times before, his work is part of a long tradition of experiments, which goes all the way back to a lot of Russian composers and technicians as well as the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. Actually, what looks futuristic today was at one time, long ago, the direction electronic music seemed to take in general: Some of the earliest Synthesizers worked with light impulses and some of the earliest music was recorded on film strips. So you would transform sound into light waves and then record them onto celluloid through photographic processes. Vice versa, there were very early visual Pianos which you would play with a regular keyboard, but which would create projections on a wall by sending light through a series of optical discs. And there’s another great example of the interrelatedness of image and sound on Derek’s homepage: Composer Daphne Oram developed a technique of painting little sketches and figures on 35mm film and using this as source material for her music – coincidentall called Oramics.

And just like there is a long tradition of working between the worlds of visual and sonic arts, there is actually a rich tradition of specifically using the overhead projector. Entire festivals have been built around the device, such as the „Art of the Overhead“ in Sweden, which consisted of seminars, workshops, performances and a psychedelic closing party. Tonewheels was, in fact, planned during a similar event called "Kunst & Musik mit dem Tageslichtprojektor", where artists from different fields came together to come up with creative solutions. Derek certainly has. (By Tobias Fischer / Download PDF)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

October 31TH 2009: Whatnight #3 DATA