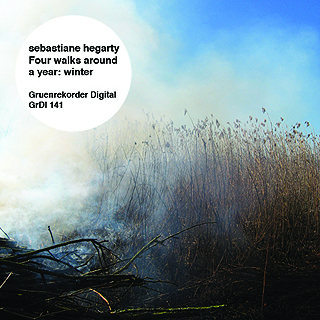

Four walks around a year: winter | Sebastiane Hegarty

winnall moors soundwalk

GrDl 141 | Gruen Digital > [order]

MP3 & FLAC

The final perambulation of the winnall moors quartet opens with the anonymous chat of conversation. Voices borrowed from the Wessex Film & Sound Archive provide an anecdotal entrance to the moors, flooding the landscape with history. Tales of previous winters accompany the listener out into a frozen dawn, occupied only by the occasional crack of ice and carrion caw. Acoustically the landscape lingers somewhere between presence and absence. Underneath the voices, my own steps proceed slowly across a frosted boardwalk, haunting the landscape with the weight of movement. The oscillation of presence suggested by my fragile steps and the disembodied voices, casts a pall of impermanence over the moors. This transience enters into the very substance of the landscape: that which once flowed now solidifies, that which was then solid now melts that which was concrete is becoming vapor.

The crystallized air underfoot, traps within its photograph my own footfall and the tracks of animals now absent. The soundscape is shushed with the crackle and fizz of thaw as ice crystals soften into the hurry of water. A dissolving chalk sample taken from the bed of the River Itchen, adds to this harmony of quiet transubstantiation. Effervescent bubbles of ancient CO2 escape from the fossilised remains of Coccolithophores: microscopic creatures that lived in the warm prehistoric oceans that once covered now visible land.

The archeological dig of this sonic dissolution serves only to reinforce the ephemerality of the landscape. Just as the intimately close cackle of fire splits the felled substance of trees into aerial particles of static: the chemical process of combustion emitting audible heat and light. For the blind theologian John Hull, the acoustic world is temporal: sound comes and goes, taking place with it. As a Chinook helicopter flies through winter, it takes our ear toward the edges of place, extending the perimeters of the moors and of listening itself. Not only does the hypnogogic drone of the aircraft, remind the listener of the agency of war and events beyond the local geography of the reserve, it also extends the boundaries of the landscape perceptually. As I listen to the drone slowly fade into silence, it takes my listening away form here and into the inaudible and invisible, the peripheral nothing of distance. As this final quarter draws a year to its close, the damp tick of rain on a barbed wire fence, washes away at the notion of place as bound and measured, the fluidity of its percussion echoed in a xylophone of wood piling. Winter concludes and disappears behind the whining arc of a barn door closing. In the noise of this enclosure, place is at once disclosed and abandoned, in the words of John Hull: ‘Sound is always bringing us into the presence of nothingness’ (John M. Hull, Touching the Rock, 1991).

There is something intrinsically melancholic in these four walks around a year, and in particular the insubstantial quiet of winter. Perhaps it is the lack of significant audible presence, which seems to make nothing tangible. Or is it the loss of time that recording imposes upon this hush, reminding the listener that what was once now, is now no more? Perhaps it is something more personal. As I listen I remember my presence and hear my absence. Through the act of recording I have simultaneously traced my movement through the landscape and marked my disappearance from it: I have become a ghost listening to myself not now there.

sound descriptors: a list of sounds as they appear on the winter walk

Tales of winter, dawn on winter solstice, dawn on Christmas Day, carrion caw, footfall on frosted boards, ice cracking, snow melting, gate opening, footsteps on snow, melting ice, mini-stream flowing, wire in the river, water hole, river hatch, children pond-dipping, pond dripping, chalk sample releasing Co2, smoke, crackle and flame, branch on fire, fire-break, willow weaving, Chinook drone, rain on wire, rain on gate, sawing wood, tying bundles, shower of woodpile, mending fences, pulling nails, chainsaw, wood piling, walking through a puddle, a barn door closed.

Background

The Winnall Moors soundwalk project was made in collaboration with Hampshire Wildlife Trust (HWT). The project began in the winter of 2010, with the aim of creating a soundwalk based on recordings made in the Winnall Moors conservation reserve over the period of one year. Extending the recording process over this timescale, allowed the discrete temporal patterns of the landscape to become apparent. The inclusive nature of the sounds collected, reflect both the complicated topography of the reserve, which is at once a shared public space, a historic and natural landscape and an area of encircled wilderness.

As the project progressed, it became apparent that composing one soundwalk for the whole year would be restrictive. It seemed more appropriate for there to be four walks, responding to individual acoustic character of the years celestial quarters: winter, spring, summer, autumn. The temporality of the sonic environment is reflected not only in the migratory, seasonal wildlife sounds, but also in the calendars of, local, human and conservation activity.

The duration of each soundwalk is set at twenty-five minutes, which roughly corresponds to the time it takes to walk a full circuit of the moors reserve. For the purposes of the HWT, the soundwalks provide a form of poetic audio guide; a sort of headphone transit, that may allow the previous and present sonic landscape to intertwine.

I would like to extend my sincere thanks to all the employees, wardens, scientists and volunteers at the Trust and in particular, Martin De Retuerto, Rachel Remnant and David Eades for their help, inspiration and support.

1 Track (25′01″)

Field Recording Series by Gruenrekorder

Gruenrekorder / Germany / 2014 / GrDl 141 / LC 09488

Richard Allen | a closer listen

How well do you know the soundscape of your own neighborhood? Are you in tune with the seasonal changes, the cries of different birds, the direction in which they migrate, the flow of local river banks and drainage systems? Do you know when the neighbors come home from work and when their children leave for school? Do you know their names, or the names of the trees in your yard, or the thickets that grow behind them? What creatures live on your property, and what sort of sounds do they make? Where do they go in the winter ~ do they migrate, burrow, or die?

These are the sort of questions that interest Sebastiane Hegarty, whose series Four Walks Around a Year has just drawn to a close. His 25-minute walks around the Winnall Moors Preserve have now been captured for all generations, one recording for each season, each recording combining the sounds of multiple forays. Gruenrekorder’s website provides an elaborate description of the walks, along with complete lists of identifiable sounds: much more than one might guess without prompt. When listening to the project in full, one experiences an entire year in a hundred minutes.

05Here’s the sound of footsteps on hardened ground, and birds singing their joy at the returning sunlight. It’s spring in the reserve, and there’s plenty of life in the moors. The African warblers have just returned; the workers are at their posts; the water is flowing freely in the river. Human equipment can be heard in the distance, never far from nature. Spring is a time to check the reserve and to see what has survived. Has the winter been harsh? Have all of the residents made it through? Has the grass received enough moisture to sprout? The people sound as happy as the birds. The layers are being shed, the windows are being opened, the populace is venturing outside. Children are gathering, crying, playing. ”Don’t drop it on its head!” warns an amused gentleman; hopefully the child has not captured a swan.

06Will summer be different? Indeed. Again we begin with footsteps and birds, but the soundscape has subtly changed. Hegarty refers to the turnover as “calendars of sounds”. Summer adds grasshoppers and wasps, ice cream trucks and active construction. A brief downpour affects the river and the leaves. As the initial burst ends suddenly, one remembers that this is not a single walk, but a patchwork; sounds are moved around in order to highlight their properties. Hegarty also writes about the absence of sound: “the ghosts of sounds no longer here.” It’s harder to hear what’s absent than what’s present, but the release trains us to concentrate and remember. The different timbres of precipitation make this the most immediately compelling of the walks, but “Wednesday evening bell practice” contributes an especially lovely angle. No offense to humans, but the lessening of voices in the summer walk is a draw as well.

02To autumn now: crunch, bird, we’re off again, a similar introduction launching into the reverse of spring. Now the birds are saying their goodbyes, morose perhaps at the thought of so much travel. Or perhaps this is simply human projection. As Hegarty notes, the water sounds different: thinner, colder, in the author’s words, “sharp and slightly angular.” Shorthand radio conversations are interspersed with personal exchanges; the birds seem to retreat, having more important things on their minds. ”A very good day today”, a woman declares. The traps have been set, more to help the local animals than to harm them, as conservation is frequently ironic. The natural soundscape is clearly quieter than the preceding installments, as the aforementioned ghosts have become obvious.

05And finally to winter. The final installment begins with wintry tales, rescued from the archives. ”Before this war we used to go skating”, reminisces an older man. And then it’s frost, ice, snow, and rain. Now that one has been trained, one notices the subtraction of flocks. Individual birds call to one another, either hardy or left behind; but the sonic field is wide open. When they are suddenly pulled from the recording in the fourth minute, one can’t help but wonder what has happened. Chalk, CO2 and crystallized air are amplified in the resulting crevasses. By the end, Hegarty himself grows melancholy, writing, “I have become a ghost listening to myself not now there.” The winter walk is a lonely walk, but it is not empty; to enjoy it, one needs the mind of Wallace Stevens (“The Snow Man”):

For the listener, who listens in the snow,

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.

link

Nathan Thomas | Fluid Radio

Sebastiane Hegarty’s year-long project “Four Walks Around A Year” draws to a close with the final winter instalment, which takes its place alongside the previously released spring, summer, and autumn episodes. Each documents in audio form a season in the life of Hampshire’s Winnall Moors, including both human and non-human activities. At the beginning of “Winter” we hear an archival recording, seemingly made not long after the Second World War, in which elders recount memories of ice hockey matches on the frozen moors. Sounds of cracking ice, crunching snow, and quiet, clear birdsong follow, interspersed in the general manner of the series with the voices and noises of humans at work and at play.

Immediately apparent is just how quiet these winter field recordings are, especially compared to the other three episodes in the series. Every noise is isolated against the blackest and most silent of backgrounds. Hegarty interweaves anthropological material with sounds chosen for their particular acoustic properties, mixing radio documentary with phonography. This approach underscores the ways in which everything animates and is animated by the social, in a sense becoming social itself, yet without this in any way exhausting the extent of its meaning. One gets a sense of how important the moors are to people, and how important people are to the moors. The drone of a Chinook helicopter is as much a part of this world as the melting ice, the burning branches, and the voices of humans as they dip for pond life or repair fences. At the same time, however, the crackles, clumps, trickles and caws are granted their own space to sound, set at a remove from human narratives; even the voices are often mixed low enough to become unintelligible linguistically, though not tonally.

This framing of multiple social and acoustic elements in different constellations of sound is perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the whole project, and one of the things that makes repeated listens so rewarding. Winnall Moors becomes a space criss-crossed with countless actual, remembered, and imagined paths, marked by tracks and traces both human and non-human. The format of several seasonally-located recordings of the same place makes this kind of constellation-building possible: a picture builds up over the year. As with some of Hegarty’s other works, such as the dissolving of chalk in vinegar heard on “Eight Studies of Hearing Loss”, the gradual sedimentation of geological time becomes quietly audible.

link