Gurs. Drancy. Gare de Bobigny. Auschwitz. Birkenau. Chelmo-Kulmhof. Majdaneck. Sobibor. Treblinka | Stéphane Garin & Sylvestre Gobart

Gruen 085 | Audio CD > [Sold Out]

MP3 & FLAC > [order]

Reviews

Recent pictures and sound recordings realised on the grounds of confinement, deportation and extermination of the Second World War, in France and in Poland.

The extermination perpetrated by Nazi Germany and its collaborationist countries against those undesirable populations (Jews, homosexuals, tziganes, mentally and physically handicapped people…) provoked a real cataclysm within our civilization because of its method, its singularity and its extent.

What memory do we keep alive today of those events, at the time of multiple commemorations, memorials and other enclosed memories.

Our artistic move aims to break off with the iconography which conditions our collective memory as much by the medium as by the contents of the pictures and the sound. What matters here is to attempt to recover and to reinvest that memory. The distance that separates us from the past tragedies increases the risk of a ritualization or a “monumentalization” of the memory, and that is the reason why we need, through art, to feed the visual memory of extermination.

The deliberate choice not to work on any visual element that refers to the systematic iconography of the camps endeavours to create, with the sound, that restraint which is essential to reverence, as it is the signature of what happened.

CD #1

1. Gurs. Internment camp. February 25th 2007

2. Drancy. La cité de la Muette. January 27th 2007

3. Bobigny. Train Station for deportation. May 27th 2006

4. Auschwitz-Birkenau. Judenrampe. February 26th 2006

5. Majdaneck. Men’s showers. Gas chamber. August 15th 2006

6. Auschwitz. The square of the orchestra. February 20th 2006

7. Auschwitz. Krematorium I. February 20th 2006

8. Krupp AG. Arms Factory. February 22th 2006

9. Auschwitz. Roll call. February 20th 2006

10. Auschwitz. Block 11. February 20th 2006

11. Oscwiecim-Krakow. Train. February 23th 2006

CD #2

1. Majdaneck. Common graves. August 15th 2006

2. Birkenau. Krematorium V. February 22th 2006

3. Sobibor. The platform. August 17th 2006

4. Birkenau. Block 1 (SK). February 23th 2006

5. Sobibor. The village. August 16th 2006

6. Chelmno-Kulmhof. Jewish place of pilgrimage. August 10th 2006

7. Treblinka. The forest. August 12th 2006

8. Krakow. The main square. February 23th 2006

9. Radivyliv. Grade crossing. August 22th 2006

20 Tracks (111′40″)

Double CD (500 copies)

|

|

|

|

|

|

bruitclair.com & gruenrekorder.de

BRUIT CLAIR RECORDS/PARA_SITE (France) / BC06

Field Recording Series by Gruenrekorder

Gruenrekorder / Germany / 2011 / Gruen 085 / LC 09488

Alexandre Galand | Le Mot et le Reste

@ „Field recording, l’usage sonore du monde en 100 albums“

Stephen Fruitman | Igloo Magazine

One of the many things that made Claude Lanzmann’s nine-hour “Shoah” (1985), so memorable was the fact that for the first time in a documentary about the Holocaust, no historical footage was used to illustrate the gruesome tale. Instead, Lanzmann talked to victims, bystanders and perpetrators in their homes, places of business, or returned with them to the killing grounds in the present day. This simple method served to remove the historical barrier between today and the black-and-white, nearly incomprehensible then.

Stéphane Garin and Sylvestre Gobart have made sound recordings from the places of confinement, deportation and extermination in France and Poland as they are today. Garin has worked with musicians as diverse as Mortiz von Oswald and Opéra du Rouen and scored the animated film “Persepolis.” Photographer Sylvestre Gobart has shown his work in Spain, France, Senegal, the US, Argentina and Guatemala. Since 2005, the duo have been plumbing the memory of extermination. As they explain, they are attempting to do what Lanzmann did but with indirect historical recounting: “Our artistic move aims to break off with the iconography which conditions our collective memory as much by the medium as by the contents of the pictures and the sound. What matters here is to attempt to recover and to reinvest that memory. The distance that separates us from the past tragedies increases the risk of a ritualization or a ‘monumentalization’ of the memory, and that is the reason why we need, through art, to feed the visual memory of extermination.”

We hear cars travelling past the interment camp in Gurs. We hear schoolchildren in Drancy. We hear visitors being guided through the men’s showers and gas chamber at Majdanek. A lone crow perched and peeved on Crematorium I at Auschwitz. Water leaking onto the floor of an abandoned Krupp arms factory. Maintenance work being performed in Block 11. A ridiculous cabaret version of “Kalinka” being piped out of some shop en route to the graveyard of Majdanek. A bonfire outside Crematorium 5 in Birkenau. Weather, commuter trains, backhoes. People chattering, sharing thoughts, pleasantries and banalities with each other in French, English, Polish, Hebrew. The longest piece is the fifteen-minute ´Chelmno-Kumholz: Jewish Place of Pilgrimage,´ a mix of sorrowful folk and cantorial songs, where the first gassings, using vans pumping their own exhaust fumes into the lungs of their human cargo, were undertaken.

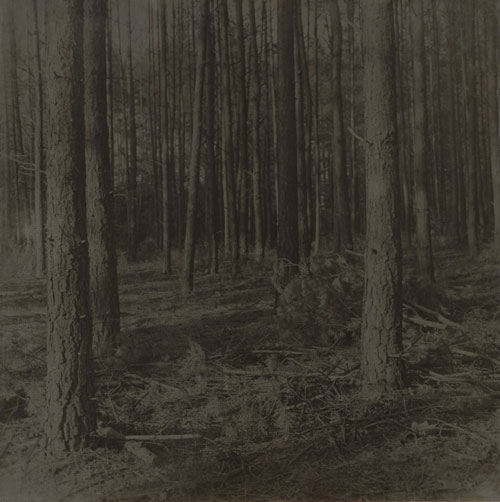

We hear, in other words, life going on. A series of dreary, streaked photographs taken when the recordings were made accompanies the discs and enhances the experience. They too are bland in subject matter—a parking lot, roadway signs, but predominantly pathetic, thin stands of trees—and as such, speak volumes about the nothing that is left to see.

The project bears dignified witness. Selected and sequenced but unmixed, these recordings mediate direct experience, the most profound of which may be the endless nine minutes of wind tearing through the dead, limbless forest of Treblinka.

Martin P | Musique Machine

This double cd album is quite a sumptuous package, containing an essay (reprinted with French and German translations) as well as numerous photographs. As you will no doubt have guessed from the title, the release concerns the geography of Nazi Germany’s attempts to eradicate undesirables: the camps and industrial apparatus that transported victims to death or imprisonment.

So, the essay discusses Garin and Gobart’s intentions to avoid the “spectacular” iconography of these events and instead encourage a more meaningful, personal relationship with those memories. Thats clearly an excellent idea, but their solution is far from perfect.

So, we have a series of rather beautiful, grainy photographs; taken at pertinent sites, but not adhering to the “standard” imagery associated with concentration camps/etc. Accompanying this are nearly two hours of field recordings, also from those pertinent sites. To be succinct – and arguably dismissive – the photographs are indeed pretty, but the audio recordings are devoid of any real sonic interest. “Bobigny. Train Station for deportation. May 27th 2006” has some interesting watery gurgles, whilst “Madjanek. Men’s showers. Gas chamber. August 15th 2006” has a testing section of silence (between intrusions of subdued tourist chatter); but there’s precious little to justify the presence of the cds. So, given this lack of content, we might ask the point of releasing the album. The answer remains in the last element of the trio: the essay.

I was talking with a friend a while back, about music and texts; and at one point he laughed and exclaimed “Its like field recordists – they love their words”. (He said this as someone who primarily concerns himself with field recording, on a sonic and theoretical level.) Unfortunately, for much of the time, he’s quite right. A lot of field recordists do seem driven to text, to justify their works. Certainly, here, the essay would appear to be the actual release. It discusses the desire to juxtapose past and present and use “abstraction”, via the field recordings, to encourage contemplation of the tension between past and present; thus achieving a fuller insight/understanding/response to those past events and their memory. This, as I said above, is entirely commendable; and indeed, I could put myself into a contemplative state with the recordings – but it has to be asked: “Is “Gurs /…” the best tool for this purpose?” Alas, the whole project reeks of detached academia. The essay itself is written in clumsy, theoretical language; apparently designed for an audience no different from the artists. You might argue it was, indeed, written for field recordists interested in the theoretical nature of their discipline. The entire release is unfortunately evident of some of the “conceits” of field recording: Garin and Gobart “took the time necessary to faithfully capture the acoustic singularity of every location”… but then used an archaic method to produce a series of photographs all sharing a similar, grainy, textural quality. It might be argued that this plays with ideas of present day realities and the visual qualities of old photographs, but really its the old “audio clarity is god” bugbear. Sonic information has to be represented without manipulation or interference, but that privilege isn’t always extended to accompanying art-forms.

So, as you can tell, I have little good to say about this album. The whole venture works on paper, but it needn’t have gone beyond that stage. I don’t feel that its rigorously realised, either. Despite insisting on no “iconographic” images, there’s a photograph of a crematorium chimney at Auschwitz – images don’t come more iconic than that. The essay translations into French and German are an interesting touch, promoting the album as a serious, almost monolithic statement – yet why no other languages? Certainly a Polish translation would seem a given, if nothing else. Also, accepting the presentation of “Gurs /…” as a weighty, serious document, why are there two pieces at the end, sectioned off as “Extra Tracks”? Given the nature of the subject matter, and the seriousness with which the artists wish the album to be received, this seems at best superficial and at worst puerile. Indeed, the implication could be further drawn, that the audio pieces came first, with the rest of the package following – whereas the essay would dictate that its words were the seed of the project.

(As a footnote, two observations: one serious, one absurd. For seriousness: there’s always a danger with work in this area, of contributing to the general notion of e.g. Jews as victims and victims only. However, its important to remember that there was resistance, organised and otherwise, to the Nazi’s population “cleansing” – indeed, the work of the Jewish resistance (and especially the post-war DIN) could be brutal and severe. For absurdity: six and half minutes into “Treblinka. The forest. August 12th2006”, the windy solitude of the forest is apparently broken by someone burping.)

link

Bobby Power | foxy digitalis

Stéphane Garin & Sylvestre Gobart’s collaborative compilation of field recordings is a harrowing experience. Described as a collection of “recent pictures and sound recordings realised on the grounds of confinement, deportation and extermination of the Second World War, in France and in Poland,” the finished product is a work provocation and meditation. Accompanied by a lengthy essay outlining the project and thick-stock black-and-gray photographs from each scene featured in the recordings, the two-discs are maxed out with field recordings from a number of stigma-riddled settings. The recordings were recorded with “no direction of the events,” or no prepared production techniques, and “include no mixing” or post-production. Listeners may be hesitant to dive in given the subject matter and sheer amount of audio (just under two-hours of recordings), but the overall impact is powerful, to say the least. Decontextualizing (or recontextualizing?) our collective memory of some of the worst moments and events in human history, with physical artifacts and settings fully tangible to anyone with interest. It’s a captivating experience if you can muster the will for it.

Jérôme Provençal | MOUVEMENT

La mémoire neuve

Parvenir à ne rien brusquer ni contraindre. Savoir reconnaître l’instant juste. Refuser de transiger. Accepter de n’être qu’un opérateur – mais d’une extrême rigueur. Garder en tête que « rien n’a eu lieu que le lieu ». Ne surtout pas chercher à faire dire – ce qui revient presque toujours à faire taire. Laisser au contraire affleurer simplement, avec la conscience aiguë des efforts immenses que réclame ce « simplement », la silencieuse parole du monde. Se (re)découvrir capable d’ouvrir les yeux et les oreilles, de regarder le vent souffler, et d’écouter l’eau s’écouler. Apprendre à étreindre la lumière.

Ces préceptes – qui, si nous parvenions à les appliquer, nous aideraient peut-être à toucher au coeur de la vie – semblent avoir guidé Stéphane Garin (musicien, multi-instrumentiste et membre de plusieurs ensembles, dont l’ensemble Dedalus) et Sylvestre Gobart (plasticien oeuvrant dans le domaine de la photographie et de la vidéo) tout au long de leur projet commun, doté, en guise de titre, d’une liste de noms de lieux : Gurs – Drancy – Gare de Bobigny – Auschwitz – Birkenau – Chelmno-Kulmhof – Majdanek – Sobibor – Treblinka. Partant du sud-ouest de la France, dont Garin est originaire, lui et Gobart ont parcouru ensemble le sinistre itinéraire qui, passant par Drancy et Bobigny, aboutit aux camps de la mort nazis installés en Pologne. Au total, le projet aura duré six ans. L’un a pris du son, l’autre des photos, mais surtout ils ont pris du temps – la plus précieuse de toutes les matières. Stéphane Garin : « La règle indissociable de ce projet était le temps. Le temps de comprendre un lieu, de s’en imprégner, le temps de le respecter, puis le temps de lui prendre sa moelle osseuse sonore. Pour ensuite écouter, noter, trier puis choisir en fonction de la musique des sons du lieu. En fonction de mon écoute sensible.» D’abord présenté sous forme d’installation, leur projet donne maintenant naissance à deux CD d’enregistrements sonores, avec lesquels dialoguent une quinzaine de petites photographies anthracite, montrant des paysages exempts de présence humaine. Coédité par le label français Bruit Clair (1) et le label allemand Gruenrekorder, ce disque s’inscrit dans la sphère dite du field recording (enregistrement de terrain), à l’intérieur de laquelle le processus créatif repose sur un traitement minutieux du matériau sonore. Tendant vers une forme d’abstraction, ces enregistrements traduisent pourtant un rapport au monde on ne peut plus concret. De fait, dans leurs prises de son comme dans leurs prises de vue, Stéphane Garin et Sylvestre Gobart manifestent un désir palpable de saisir le monde et d’en offrir une perception patiemment mûrie. Arpentant ces lieux ô combien chargés d’histoire, ils ont tâché d’en extraire l’essence, au-delà ou en deçà des multiples couches de lecture déposées depuis 1945, en s’approchant au plus près de la vie ordinaire – d’où une trame sonore faite uniquement de choses banales (l’aboiement d’un chien, le crissement de graviers, le murmure d’un poste de radio, le bruit d’un moteur de voiture…), a priori sans importance, mais qui sont l’expression même de la vie. Capter ces choses aujourd’hui sur les lieux où, hier encore, régnait un silence de mort, n’est-ce pas la plus belle manière de conjurer la barbarie nazie?

Oliver Laing | Cyclic Defrost

I suppose I should give this collaboration between Belgian visual artist Sylvestre Gobart and French musician (and in this case, sound-recordist) Stéphane Garin its exhaustive full title – Gurs, Drancy, Bobigny’s train station, Auschwitz, Birkenau, Chelmno-Kulmhof, Majdaneck, Sobibor, Treblinka. Phew; and it’s an exhaustive listening experience, as extreme, in its own way, as the pure digital sine wave manipulation of my previous review of Cyclo. Gurs…Treblinka consists of unmixed, unmolested field recordings; the sound of everyday life and nature combining, in an attempt to reconfigure and decontextualize the powerful historical memories of the atrocities committed by Nazi Germany during the Second World War. I’m in the habit of zeroing in almost solely on the audio component of a release, maybe with a perfunctory comment about the cover art or tactile nature of the packaging, if this seems relevant. In the case of Gurs…Treblinka, I needed to treat the package as a coherent whole, pawing over the zinc-saturated grey scale images of the various locales in order to link the visual and audio components of the work. Gobart’s photography has a solemn and steely feel to the reproductions contained within on CD-sized individual pages.

Gobart and Garin chose not to record at the central, obvious location at the different sites, rather detouring to a forgotten glade or peering over a wall constructed after WWII, in order to demonstrate that life must go on. The extermination camp at Sobibor in far-eastern Poland, is represented by sounds of heavy machinery, tools being dropped, idling motors… The visual side shows a heavily laden train and a sandy track torn asunder by heavy tyre-tracks. A place of Jewish pilgrimage, Chelmno-Kulmhof was another Nazi camp in Poland. Garin’s field-recordings include subdued voices, crunching footsteps in the snow and a distant, somewhat haunted, yet hopeful song of redemption.

The artists state their desire to break with the dominant iconography of the Holocaust, replacing the collective memory of dank gas chambers and mass graves with a new psychogeography of the locales involved in an intensely dark chapter of human existence. Without wanting to trivialise the subject matter, or the artistic intention behind the Gurs…Treblinka project, the audio component did nothing to hold my attention. Rather, I slumbered and re-awoke to certain passages throughout the nearly two-hour duration of the double CD album. As an interdisciplinary artistic statement, Gurs…Treblinka carries a powerful emotional punch; it’s just not something I’m particularly inviting of into my life. Garin and Gobart demonstrate an unmistakable self-belief in their approach. Admittedly, my relationship with field-recordings is somewhat ambivalent, and my tastes veer towards the more heavily processed end of this audio niche, but even with some heavy contemplation on a blackened past, Gurs…Treblinka was, for this reviewer, an exercise in patience that was ultimately unrewarding. Find out for yourself here.

Dan Warburton | PARIS Transatlantic Magazine

Well, the title says it all, really. Merely reading the word Auschwitz, let alone Treblinka, Birkenau etc. has already conditioned your response to this album of field recordings made in the abovementioned places. As an example of how titles can affect one’s judgement of a work of art prior to experiencing it, this is even better than Penderecki’s celebrated Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima. If Stéphane Garin (the sound recordist) and Sylvestre Gobart (of whose photographs more later) had called their collaboration something like „Our European Holiday“, I doubt anyone would have paid any attention to it all. I know I certainly wouldn’t have spent as much time with as I have. As such, I suppose the artists have achieved what they set out to do, make me reflect on the Holocaust: „The relationship between sound and image is at the centre of our work. Through ordinary elements (car engine, dog barking…), sound is what enables the audience to slip gradually towards a certain abstraction, providing a necessary distance for us to penetrate further into thought.“

I seriously doubt whether Messrs Garin and Gobart subscribe to the theory that the historical events that occurred in these places somehow still resonate in the sounds that inhabit them today – their accompanying notes are, after all, undeniably sincere (if a tad arty-farty) and refreshingly free of all that hauntological penmanship – but I’m sure they’re aware of, and quite possibly influenced by, their compatriot Guy Debord’s concept of psychogeography, which, you will recall, he defined in 1955 as „the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behaviour of individuals“ (though I’ve always wondered what those „precise laws“ were). Even so, this project is no dérive; Garin and Gobart didn’t just wander into the showers and gas chambers of Majdaneck like a pair of latterday flâneurs – they went there with the precise intention to document what they heard and saw.

Of course, it’s perfectly natural – and inevitable, once you’ve read the album title – to read in (hear in) different levels of meaning (I won’t bore you with that old John Berger Van Gogh story from Ways of Seeing again). Cawing ravens above the Auschwitz Crematorium become grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt, and ominous birds of yore croaking „Nevermore“, and the French schoolboy’s playground tales in the cité of Drancy („il s’est battu contre Abdullah!“) reminds me of my friend Olivier Brunet’s chilling lines in his Fanny’s Wedding: „Childhood is something beautiful, but also full of wickedness… [i]t doesn’t last, they grow up, become something else, war criminals, hideous fat men, bitter old women, liars, cowards, and finally corpses.“ Other reviews of the album I’ve read can’t resist the temptation, either: Brian Olewnick hears distant echoes of jackbooted Nazis marching across the square at Auschwitz, and for Richard Pinnell, „the clattering rhythm of moving trains brings with it a disturbing suggestiveness that such a sound wouldn’t have in another context“ (hmm, remind me to sell my copy of Steve Reich’s Different Trains – I have no desire to listen to that again). But Vital Weekly’s Frans de Waard is having none of it: „Just as much as I think that other projects from all of man’s wrong doings, like nuclear disaster sites, is a mere con to sell a project to the world of art. There is not much difference between an empty room and an empty room. The field is innocent, so the forests of Drancy, Auschwitz, Birkenau etc. are as innocent as those around my corner – it’s men idiocy who is responsible the activity that went on there [sic]. You wouldn’t know these sounds came from concentration camps, if you didn’t read it.“ And, of course, he’s right: a bird doesn’t sing a different song just because 65 years ago hundreds of human beings were exterminated and thrown into a mass grave lying under the tree whose branch it happens to be perched on.

As Michel Chion observed in his recent Wire Invisible Jukebox, „It’s funny that albums of field recordings [..] often include photos of the places as well. But sound and image aren’t the same thing. Look out of this window at the rooftops and you know you’re in Paris. But the sound in the courtyard below could be anywhere. Cities sound more or less the same the world over.“ Gobart’s photography happily avoids the usual Holocaust imagery – no Arbeit Macht Frei here – yet its austere black and white (make that black and grey-green) and conspicuous lack of people (where are those Drancy schoolkids?) strike a sombre note. Had he shot in gaudy colour, like the deliberately banal images that accompany Emmanuel Holterbach’s album reviewed here last time round, our response would be quite different.

Similarly, Garin seems to have gone out of his way to record everyday sounds – yes, as usual, there’s plenty of birdsong and traffic noise – but (ironically?) the disc’s highlights are those where a clear sense of locality is discernible: the distant string quartet in Majdaneck chugging through Eine kleine Nachtmusik with hilarious wrong notes and morphing it into Chopin, the cheesy but touching music in the Chelmo-Kulmhof Jewish memorial, the Hejnal Mariacki trumpet call from the towers of St. Mary’s in Cracow (a pleasant but hardly essential bonus track).

Such flashes of clear local colour aside, most of the sounds on these two discs could, as Chion says, have been recorded just about anywhere. These days there’s little stopping anyone with a good pair of mics and a malicious (or sick) sense of humour from recording the sounds of his own city centre, railway station and nearby woodland and selling them off as Hiroshima, Ground Zero, the Somme, Gettysburg or any other site of historical catastrophe you care to mention, the aural equivalent of this canny little business (how long before we get an album of field recordings from Miyagi Prefecture? I’m not joking here..). That said, I’m sure Garin and Gobart’s intentions are entirely noble. But the good folks at Gruenrekorder should have exercised a little more quality control somewhere along the line: 45 minutes of this stuff would have been perfectly sufficient. When it comes to the Holocaust, a little goes a long way. Ever seen Nuit et brouillard?–DW

Odile Faure | SudOuest

De Gurs à Treblinka

Le percussionniste Stéphane Garin livre des cartes postales sonores des camps

On le remarque peu à l’Orchestre de Pau, caché au milieu de ses percussions, mais sa participation est essentielle. Le disque coffret qu’il vient de coproduire ne se remarque pas non plus mais il est utile pour la démarche de mémoire. Stéphane Garin a arpenté neuf camps d’internement, de déportation et d’extermination, avec son micro, accompagné d’un photographe bruxellois, Sylvestre Gobart. Le travail leur a pris plusieurs années avant d’aboutir à deux CD audio accompagnés d’une collection d’images patinées de gris.

« Cette idée est partie de la musique. Je me suis de plus en plus intéressé aux sons environnants à la façon de John Cage. Ce travail a croisé ma passion pour la période de la déportation », explique Stéphane Garin, 37 ans, qui habite Bayonne. À 12 ans, ses parents l’empêchent de regarder « Shoah », de Claude Lanzmann. Il commande quand même la cassette à Noël, qu’il obtient et regarde 35 fois. De ses voyages dans les camps, il a ramené des sons du quotidien d’aujourd’hui, des voitures qui circulent, un enfant qui joue, un ballon qui tape. Pas de musique, juste des voyages sonores.

Auschwitz, le froid, le choc

« La première fois que je suis allé à Auschwitz, c’était en 2005. J’avais acheté des micros sans bonnette anti-vent. Il faisait un froid ! – 29° ! J’y ai passé dix jours, j’ai enregistré, enregistré, puis j’ai décidé de faire un CD ». Stéphane est venu à Gurs. Sa mère, originaire de Mauléon, lui avait parlé de ce camp d’internement ouvert en plein Béarn entre 1939 et 1944, qui a accueilli des républicains espagnols, des Juifs persécutés et des « indésirables ».

« J’ai voulu tracer le parcours de la déportation de Gurs à Auschwitz. Du Béarn, je suis allé à Drancy, puis dans la gare de Bobigny et en Pologne. Certains de Gurs allaient directement à Sobibor ou Treblinka. »

Un voyage chargé pour un trentenaire. « Je ne sais pas pourquoi j’ai une sensibilité pour cette période. C’est comme ça. Ce fut un tel cataclysme, y compris dans les arts ! Il y a un avant et un après „camps“. Cela me fascine. Les bourreaux me fascinent. Comment peut-on définir un espace avec des barbelés à l’intérieur duquel tout est possible ? Comment se met en place le mécanisme du génocide ? » Le regard aiguisé par l’histoire, l’artiste a désormais du mal à admettre les « petites intolérances du quotidien ». « La peur de la différence, avec sa propagande et la crise. Plus c’est gros, plus ça marche. J’ai aussi beaucoup de mal avec la hiérarchie, le pouvoir, tout ça me fait très peur. On s’aperçoit que, dans un espace clos, tout peut être permis, ceux qui ont le pouvoir peuvent en profiter. C’est ça qui est morbide. Les camps me tendent plutôt vers la vie. Car Auschwitz ou Gurs révèlent aussi la résistance des hommes : écrire un poème et l’enterrer, donner du pain, accueillir les persécutés. Comment à – 25 en Pologne, peut-on survivre en pyjama et en sabots ? Comment on s’en sort ? C’est cela, l’énergie et la résistance humaine ! »

« Gurs.. Treblinka », de Stéphane Garin et Sylvestre Gobart, édité par Gruenrekorder et Bruit Clair. Renseignements : garin.stephane@gmail.com Le camp de Gurs est situé sur la route entre Navarrenx et Oloron. Il est ouvert en permanence.

maeror3 | maeror3.livejournal

На протяжении двух лет Стефан Гарин (запись) и Сильвестр Гобарт (фотографии) объездили всю Европу, посещая печально известные концентрационные лагеря, оставшиеся после Второй Мировой Войны, и подготавливая свой амбициозный аудиовизуальный проект, вылившийся в данное двухдисковое издание лейбла «Gruenrekorder». Нетрудно догадаться, что нас ждет на этих дисках – около двух часов «полевых записей», призванных передать современную атмосферу мест, в которых одни люди в промышленных масштабах лишали жизни других людей.

Однако ключевое слово здесь – «современную». Да, фотографии Гобарта выполнены в нарочито «старомодной» манере, сыры и впечатление производят тягостное. Другое дело, что аудиозаписи такого впечатления произвести не могут. При прослушивании альбома в голову приходят странные мысли о том, что Природа давно уже забыла обо всех ужасах войны, ветер выдул с пустых лагерных площадей крики, дождь (судя по всему, сопровождавший авторов на всем протяжении пути, так часто мы можем слышать монотонный шум капель) смыл реки крови, а земля, впитавшая их, давно уже все переварила и пустила на благие нужды, дав кому-то или чему-то жизнь. Осталась только человеческая память, и именно к ней взывают французы, записывая свои «бродилки» по крематорию Аушвица в составе экскурсионной группы, звуки громыхающих поездов, проносящихся мимо станции пересадки арестованных возле Освенцима, передавая гулкую, пустую атмосферу газовых камер и бараков Майданека. Мы услышим не только шум дождя, но и голоса многочисленных посетителей этих мест, которые с интересом внимают лекциям экскурсоводов, прерываемые бравурными маршами из громкоговорителей и рингтонами мобильных телефонов. Кто-то даже весело комментирует и смеется – люди как люди, их можно встретить везде и ничто уже не способно произвести на них сильного впечатления, особенно события, отделенные шестидесятипятилетней пропастью. Полевые записи Гарина звучат интересно, они грамотно передают пространство и четко фиксируют момент, так, что мы слышим и живо представляем себе и проносящиеся мимо машины, и сигналы далекого транспорта, и шелест листвы под ногами, и буйство раскачиваемых ветром деревьев, и тишину пустых зданий, по железным крышам которых лупит дождь – слышим, представляем и понимаем, что на эти предметы и локации вину за свершенные деяния глупо перекладывать, как глупо винить в чем-то лес и землю, на которой построили фабрики смерти. Должно звучать еще что-то в нашей душе, чтобы подобного больше не повторилось, и сделать запись этого «что-то» гораздо сложнее…

Richard Pinnell | The Watchful Ear

So then to the double CD / photographs release on Gruenrekorder by Stéphane Garin (phonography) and Sylvestre Gobart (photography). This is a fascinating release. It is titled Gurs. Drancy. Gare de Bobigny. Auschwitz. Birkenau. Chelmo-Kulmhof. Majdaneck. Sobibor. Treblinka, which might at first seem a somewhat clumsy title listing some of the sites of Nazi atrocities in World War II, but once you spend time with this work, and read the essay explaining the intentions behind it, which are about rethinking our memories and relationship to these horrible events without the iconography that has become attached to them through the media over time, then just listing the places rather than thinking up a catchy title makes a lot of sense.

The release consists then of two discs of field recordings made at sites of Nazi atrocities, and a set of fourteen prints of photographs by Gobart, originally made as light sensitive emulsion images printed onto zinc sheets. The images are thoroughly affecting, partly because the process used to form them is aesthetically very beautiful, but should we find images of such places attractive? How about when all that remains of the history of a place is buried under a snowbound forest? If I didn’t know about the historical importance of the photograph’s subject matter then I would doubtlessly have found these images very appealing. Is it right that I should question my thoughts about them now I know more about them?

The two CDs present recordings made at sites of great significance, gas chambers, prison houses, train stations used for deportation to death camps etc. Some of these remain as places now visited by the public in their hordes, so taking in the imagery that has become commonplace today, the same photos from archives, the way these places have become preserved as reminders to humanity. Some of the sites Garin and Gobart worked at though now show little to no trace of their dark history. So they also recorded at forests and village squares, where life seems to have moved on, at least on the surface.

The recordings are designed to capture these places as they are today. So we hear the trains, the footsteps of tourists, music playing, and in one thoroughly haunting piece near the end of the second disc, the virtual silence of the forest at Treblinka, Poland. Here, where almost no trace remains of the camp that saw over 800,00 innocent people exterminated, since the Nazis tried to remove it from existence once they had no more use for the place, we hear the wind in trees, the very occasional bird, some footsteps in snow, but little else. Coupled with Gobart’s images of the forest that now stands in place of the death camp the effect of listening to this piece is quite chilling, not because of anything that the recording/imagery particularly portrays, but because they allow us to listen /look and think, recreating our own thoughts on the place, with the iconography removed, relocating us with the raw emotions we feel towards such terrible human acts, rather than filtering them through standardised images and words.

This seems to be Garin and Gobart’s aim, to leave us to reunite ourselves with how we feel about the events that took place at these sites without the desensitised approach we have come to understand. As the media has an increasingly important place in our lives, whether we like it or not, it has shaped and provided a backdrop and soundtrack to our memories and feelings relating to this kind of thing. So we all attach images and thoughts to the Nazi genocides that are provided to us by the media, just as events like 9/11 have their own soundtracks and imagery. What this CD attempts to do, and to some extent succeeds in doing, is removing the media’s impact, so letting us rethink about what happened, using these seemingly everyday recordings of places and the accompanying photos as a kind of cleansing device, allowing us to consider the events in light of how these places are today, some filled with tourists, but some seemingly now ‘normal’ places. This project levels the playing field for each of them, allowing us to use just our thoughts to give meaning to them.

So, more than just a couple of CDs of field recordings, more than just music, more than just something to listen to. I found spending time with these pieces, the stunning photos and the accompanying essay to be a thoughtful, if thoroughly sobering experience. This is a very well thought through and very well executed project that deserves to be engaged with by as many people as possible.

Ron Schepper | textura

Anyone contemplating creating an artwork that invokes WWII and the Nazi regime’s ‘Final Solution‘ (more specifically the attempt to exterminate the entire populations of Jews, homosexuals, etc.) knows that delicate, emotionally charged ground will be trod upon and that whatever’s done will have to be done with circumspection. In broaching the subject, phonographer Stéphane Garin and photographer Sylvestre Gobart first considered the memories being kept alive today in light of the ceremonies and monuments that currently engender memorialization of a particular kind and then decided to create new associations by producing visual and sound portraits of internment, deportation, and extermination facilities from Gurs, France to Poland (Garin has collaborated with figures like Carl Craig and Moritz von Oswald, performed with orchestras such as the Brussels Philharmonic and Orchestre philharmonique de Radio France, and collaborated since 2005 with Gobart, a France-based photography and video artist, on the work in question).

Towards that end, they broke away from established iconography by eschewing the use of familiar photographs that convey the horrors of the camps; instead, the images they use encourage us to see the sites anew, severed from the ties to collective memory. While they may be stripped of that history, the photos by Gobart included in the release are nevertheless haunting, not only because of one’s awareness of those associations but also because they’re printed (for the CD release) as dark, duotone-like images that have a kind of chemically aged, silver-tinted appearance and thus take on an ethereal quality. Not a single person appears in photos that otherwise display trees (the forest in Treblinka), train stations (one for deportation at Bobigny), and other key sites (a snow-covered forest that was once a Birkenau crematorium, an open field at one time an internment camp at Gurs, men’s showers used as a gas chamber at Madjanek, and so on), making their already ghost-like quality even more pronounced. Such apparently untainted settings nevertheless carry the weight of history and thus paradoxically render visible within the viewer what’s no longer seen.

On the phongraphic side, quotidian sounds—car engines, clomping footsteps, barking dogs, children playing, people talking—mask the darker realities of the locales, enabling the listener to ease into a relaxed state that helps facilitate reflection upon the contents of the field recording portraits. No one would ever think that one is visiting a site of common graves in Majdaneck when the sounds of classical music, dogs, people, and traffic fill the air. Likewise, a pastoral idyll filled with chirping birds turns out to be the site of an internment camp at Gurs. On the other hand, the sorrowful singing that appears towards the end of the recording made at Chelmno-Kulmhof, a Jewish place of pilgrimage, suggests a powerful connection to its setting, and hearing the clattering rhythms of moving trains brings with it a disturbing suggestiveness that such a sound wouldn’t have in another context. Certainly the reverberant echo of footsteps trudging through Block 11 at Auschwitz is disturbing enough all by its lonesome (the corresponding photo is the only one of those included where everything is buried in darkness save for three overhead lights). At times, imagination and reality collide. In the first disc’s eighth track, for example, the sound of water drizzle immediately invokes the association of the men’s showers at Majdaneck that were, in reality, a gas chamber, but it turns out that we’re actually at an arms factory in February, 2006. Other sites where recordings were made include a train station for deportation at Bobigny, Auschwitz crematoriums. Though disc two’s ten-minute Sobibor recording (construction sounds dominate) is twice as long as it needs to be, missteps are few in what cumulatively impresses as a beautifully designed and powerful aural-visual document by the collaborators.

Frans de Waard | VITAL WEEKLY

The other new release by Gruenrekorder I somewhat was reluctant to hear. Not because of its content – field recordings from Nazi concentration camps – but because of its intention. It has photos and sounds from various locations, but the whole thing just gives me the creeps. ‚We wish to call up what cannot be seen any longer, but also to show that there is nothing left to see, in order to break with the vision we have grown accustomed to, by a certain collective memory, eager for spectacular‘ or that arty farty speak of ‚our choice was dictated by a will to create abstraction and to break formally with an iconography that conditions our memory‘. Just as much as I think that other projects from all of man’s wrong doings, like nuclear disaster sites, is a mere con to sell a project to the world of art. There is not much difference between an empty room and an empty room. The field is innocent, so the forests of Drancy, Auschwitz, Birkenau etc are as innocent as those around my corner – it’s men idiocy who is responsible the activity that went on there. You wouldn’t know these sounds came from concentration camps, if you didn’t read it. Does it make the whole thing more ‚important‘, more ‚interesting‘ or even more ‚relevant‘? We should never ever forget the holocaust, visit concentration camps, read books about it, but this double CD seems very wrong to me. I conducted a small experiment in which I played some of this to various people, sometimes letting them what it was and sometimes not. Those who didn’t know, thought it was indeed just outdoor recordings, and those who did know did agree that it hardly makes a difference and it all still sounds like field recordings which could have been made anywhere. I do think however that the package is a strong reminder – never again – and a such of course its pretty well made.

Brian Olewnick | Just outside

It’s an interesting idea, laden with resonance: deal with the fact that images from Nazi internment facilities, deportation centers and concentration camps have long since,for many, especially the young, become iconic, divorced from their deep, horrific meaning. Garin (phonography) and Gobart (photography) set about to document the current state of these locations via field recordings and photos of the unspectacular, the everyday even as that „normalcy“ is imbued with what those sites, from France to Poland, have experienced.

Two discs, a dozen photos and a fine essay (in English, German and French), all presented with great care and subdued beauty. So it’s not about the sounds as such, finely recorded though they are (or the wonderful, silvered photos). As they write:

„Through ordinary elements [… ], sound is what enables the audience to skip gradually towards a certain abstraction, providing a necessary distance for us to penetrate further into thought.“

Even so, when one hears the gravelly, regular crunch of tourists boots as they „see the sights“, it’s difficult to not recall other kinds of boots. Water dripping in some interior space conjures up a dark foreboding of its own. Trucks, dogs, conversation–all take on an added patina. And when, at the beginning of the second disc, one hears an amateur orchestra working its way through „Eine Kleine Nachtmusik“, well…

A very strong document, then, not so much as a music/image release but for what the sounds and photos evoke in the consciousness of any thinking individual.

-1-800.jpg)